Acrylamide is a chemical that naturally forms in starchy food products during high-temperature cooking, including frying, baking, roasting and also industrial processing, at +120°C and low moisture. The main chemical process that causes this is known as the Maillard Reaction; it is the same reaction that ‘browns’ food and affects its taste. Acrylamide forms from sugars and amino acids (mainly one called asparagine) that are naturally present in many foods. Acrylamide is found in products such as potato crisps, French fries, bread, biscuits and coffee. It was first detected in foods in April 2002 although it is likely that it has been present in food since cooking began. Acrylamide also has many non-food industrial uses and is present in tobacco smoke

Here is the listo f food where you can find it. Fried potato products (including French fries, croquettes and roasted potatoes) and coffee/coffee substitutes are the most important dietary source of acrylamide for adults, followed by soft bread, biscuits, crackers and crisp breads.

For most children, fried potato products account for up to half of all dietary exposure to acrylamide with soft bread, breakfast cereals, biscuits, crackers and crisp breads amongst the other contributors.

Baby food (mainly rusks and biscuits) is the most important source for infants.

Some other food categories such as potato crisps and snacks contain relatively high levels of acrylamide but their overall contribution to dietary exposure is more limited (based on a normal/varied diet).

Acrylamide consumed orally is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, distributed to all organs and extensively metabolised. Glycidamide is one of the main metabolites from this process, and is the most likely cause of the gene mutations and tumours seen in animals

Currently, studies on human subjects have provided limited and inconsistent evidence of increased risk of developing cancer. However, studies on laboratory animals have shown that exposure to acrylamide through the diet increased the likelihood of developing gene mutations and tumours in various organs.

Based on these animal studies, EFSA’s experts agree with previous evaluations that acrylamide in food potentially increases the risk of developing cancer for consumers in all age groups. While this applies to all consumers, on a body weight basis, children are the most exposed age group

The storage method and the temperature at which food is cooked can influence the amount of acrylamide in different food types and, therefore, the level of dietary exposure.

- Coffee substitutes made from chicory generally contained on average six times more acrylamide (3mg/kg) than cereal-based coffee substitutes (0.5mg/kg)

- Fried products made from potato dough (including crisps and snacks) generally contained 20% less acrylamide (338µg/kg) than those made from fresh potato (392µg/kg)

- Potatoes grown in sulphur-deficient soil usually accumulate less asparagine, reducing acrylamide formation during heating

- Storage of potatoes at below 8°C generally increases sugar levels in potatoes, potentially leading to higher acrylamide levels following cooking

- Soaking potato slices in water or citric acid solution can reduce acrylamide levels in crisps by up to 40% or 75%, respectively.

- Lighter coffee roasts generally contained more acrylamide than medium and dark roasts (which are roasted for longer), potentially increasing average exposure by 14%

- Consumer preferences for crispy and brown French fries and other fried potato products may increase average dietary exposure by 64% (for high consumers, by 80%)

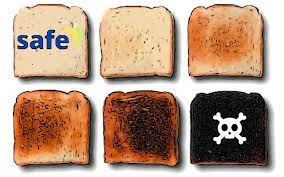

- Toasting bread for five minutes instead of three minutes can increase the acrylamide content from 31µg/kg up to 118µg/kg, depending on the bread type and temperature of the toaster. Consumption of well-toasted bread, however, only increases overall average dietary exposure by 2.4%.

Generally, since it is practically impossible to eliminate acrylamide entirely from the diet, most public advice for the consumer aims at more selective home cooking habits and more variety in the diet.

Since acrylamide levels are directly related to the browning of these foods, some countries recommend to consumers: “Don’t burn it, lightly brown it”. Varying cooking practices and finding a better balance, e.g. boiling, steaming, sautéing as well as frying or roasting, could also help reduce overall consumer exposure.

Currently, EU Member States monitor acrylamide levels in food and submit data to EFSA. The European Commission recommends that Member States carry out investigations in cases where the levels of acrylamide in food exceed so-called ‘indicative values’ set by the Commission